Small Moves

In the dream my ear is pressed up beside the dial of an enormous safe which I am manipulating gingerly in tiny moves both clockwise and counterclockwise. I am listening for movement inside the inner-workings of the lock. Sometimes my hand is on the tuning knob of a shortwave set.

Never have I considered what I might actually do with or say to whatever was on the other side of the door. I only knew that, in the process of picking the lock, I am, like Ellie Arroway in Carl Sagan’s Contact, trying through “small moves” to reach through the veil between here and what is far. Like Ellie, I’d have liked to contact a lost parent. But really the unlocking, the deciphering, the listening, the reaching, are all describing the building blocks of artistic and scientific progress.

The dream and its variants have recurred countless times over the past fifty years. It strikes me that in all those iterations I never questioned what (if anything) was within the safe. I am assuming that it must have been precious, or secret, or at least highly-prized because of the effort required to connect with it — the listening, the concentration, the thrill of being on the verge of finding out.

As familiarity with the dream has grown, I realize that it represents not just the desire to reconnect with the past but the desire to connect with the future; not just the importance of perseverance but the promise that even the tiniest of steps forward constitute a positive contribution to the human story.

It isn’t that there is all the time in the world. Being completely in the moment requires that it should at least feel that way. The black and white teeth of the keyboard. Ease. The sense of home, safety, belonging, intense familiarity, of infinite possibility. Physical pain, woe, regrets, all, all accepted; judgement suspended.

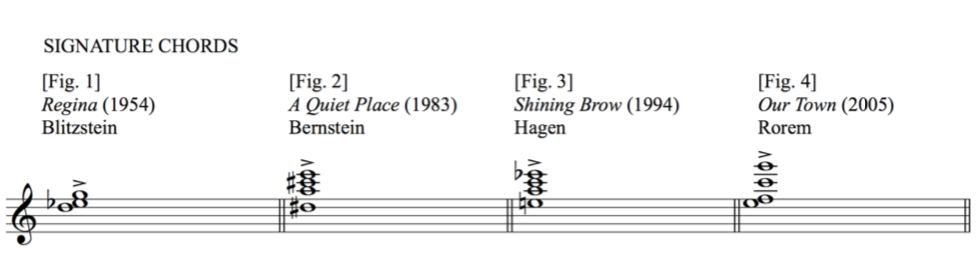

Just as the common assumption of what sonata means is falsely specific (after all, it only really means “sounded” in Italian; we take it to describe a piece of instrumental music), the word composing is generally assumed to pertain to the act of creating a piece of music, or poetry when it is really the act of creating anything by putting something together from constituent parts.

The comforting smell of freshly brewed coffee; the faint odor of old, polished wood —the instrument. The light: where does it come from? How bright is it? And the temperature: am I nude because it is hot or do I need to wear clothing? What season of the year is it? Where am I? Do I have privacy, and if I do not, am I comfortable accepting another in this space?

That composing (with a small c) a first-person essay about Composing (with a big one) will by default result in something “personal” is inevitable since an author’s sharing of personal experiences and the use of “I,” “me,” “my,” “mine” and “we” refer to a group to which the author belongs. I only know what has worked for me: Process (with a big P) is personal (with a small one); and any effective Process reflects the values, training, and individual experiences of its implementer. Subjectivity may be boring, but it is subjective to say so.

There will be a couple of what Lenny called his “reddy-blueys,” double-pointed pencils that most composers and conductors have on their worktables and pianos. Possibly some sort of vessel created by childish hands in art class — a reminder of one’s place in the fabric of a family or the simplicity of childhood creativity — with several precious Eberhard Faber Blackwing 602 pencils and the small gold-plated penknife to sharpen them that Diane Doerfler gave me in 1979. A good Staedtler eraser. My lucky Pentel Sharp Mechanical Pencil, 0.7mm, #2 Medium Lead with its teeth-marked plastic blue barrel, and the brass, bullet-shaped German pencil sharpener that Roger Zahab gave me on the opening night of Orson Rehearsed.

The power of comfort objects: the lock of Nakiro’s mane that my violinist friend kept in her violin case; the Saint Jude medal that Richard McCann kept in his breast pocket; David Diamond’s Baccarat crystal paperweight; the leather catspaw of my mother’s keychain that I carried with me until, when it literally began to disintegrate, I threw it into the northeast corner of the Central Park Reservoir, quoting Maude: “So I’ll always know where it is.” In any event, a safe space in which to Create must in itself be created. Having treasured talismans at hand can help.

Then, looking at a blank sheet of manuscript paper, I am like my hound turning in a tight circle and scratching on the couch, chuffing slightly, sniffing the result and finding it satisfactory, unspooling a long sigh while coiling into the shape of a cinnamon bun, and, finally, rooting, nestling her snout between her paws, the eyes fluttering, ready to dream.

And then, what? For a composer working at the computer confronts not the “formless void covering the face of the deep,” (a lot to unpack there) but the lightless pixels of a black screen covering the face of the digital void of ones and zeros. For the analogue composer, a blank (meaning that it in fact reflects all the colors in the visible spectrum) white page — in the West, anyway, probably covered with skeins of five parallel horizontal lines.

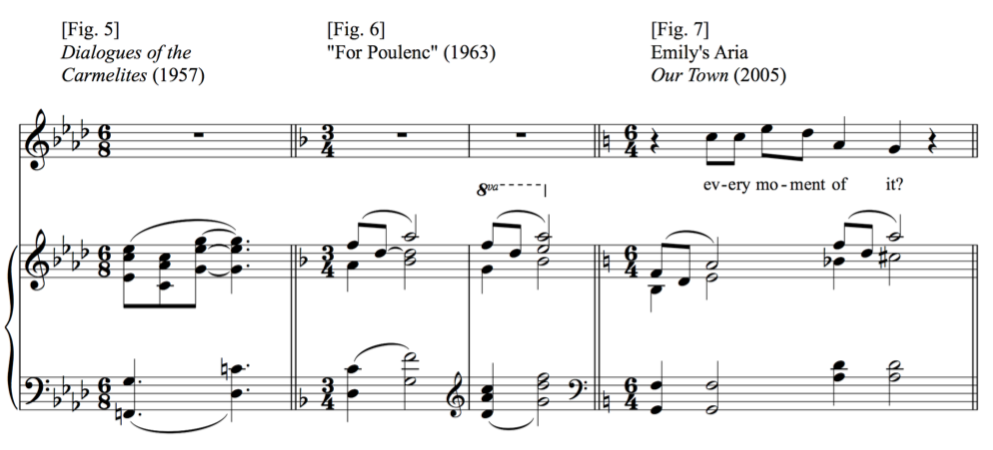

Putting Music Behind Bars

Composer David Rakowski, who sketches in pencil, described to me how he settled on his preferred manuscript paper: “In 1984 I asked Mike Gandolfi to make some paper for a piece for … I think … two winds, piano, and four strings. What I got was some perfect paper for that, plus paper for piano etudes, and string quartets. He did every line by hand. Eventually I made my own ‘Mikey paper’ in PageMaker and printed it when I needed it — nice to have the HP 5200 — yes, it was tabloid size and I like that.”

Michael Torke, when I asked him what he sketches on, replied, “I have a Sibelius file — a single page that has three systems of 4 staves each, with blank 8 bars across. I simply print out as many sheets as I need on the cheapest paper I can find so that the ink flows easily and use black and red Pilot Razor Point felt tips pens to write.”

That morning, killing time before a composition lesson with Ned Rorem at his apartment on West 70th Street in October 1981, Norman Stumpf and I had taken the subway down to Astor Place in the East Village to pay a visit to the Carl Fischer music store. Norman needed to buy a score of something and I needed music paper.

Ned remained a manual typewriter man to the end of his days — never bought a computer, much less learned how to use one. During the 80s-00’s, he typically sketched with pencil in commercially-available, spiral bound, twelve stave manuscript notebooks, occasionally using the 20-stave paper that I preferred, which I would duplicate at a copy shop near Columbia University when I made my own and deliver when I came to work for him. He then transferred his sketches by hand in pencil on to vellum, as was his generation’s preference, since their publishers reproduced these “fair scores” on ozalid machines prior to having hand-engraved published “plates” made for lithographic reproduction suitable for print sale.

I quit music copying in 2004 and therefore don’t know how he managed after that, but I, as Imogen Holst assisted Benjamin Britten, typically “set up” Ned’s “fair score” pages by transferring the obvious musical lines for him, at which point he, seated at his red dining room table year after year, would complete the task. Then I would take them to the copy shop to make safeties and then walk them down to Boosey and Hawkes’ office in Midtown. Often, I extracted the performance parts as well and proofread some of the engraved galleys before they went back to Boosey. As he got older, Ned had less energy, took less interest in, and trusted me more, and I gradually assumed a more expansive role, fleshing out orchestrations, crafting piano reductions, and so forth. All very human.

I took a flier and bought a couple of quires of King Brand MSS20 10.5” x 13.5” manuscript paper, extra heavy ivory stock, with “smooth surface for writing with ink or pencil” and a “non-glare finish.” The paper size was a little large for my piano rack, but that problem was solved as though by Deux ex Machina when I dumpster-dived a beautiful, beveled glass writing rack that had belonged to a famous neighbor on 98th Street between West End Avenue and Riverside Drive, where for many years I lived.

Cornelius Cardew and Earl Brown covered truly blank paper with abstract gestures and colors meant to evoke cries, whispers, and sobs with self-invented graphic notation that is in itself a source of aesthetic sustenance. Ishmael Wadada Leo Smith, the trumpet player and composer, developed in 1970 a fascinating graphic notation system he calls Ankhrasmation; before Augusta Reade Thomas transfers her musical ideas to standard western notation, she creates beautiful, multicolored graphic scores brimming with Miro-esque exactitude and Chagallian joy. Fluxus scores by composers like Ben Patterson and Mieko Shiomi consist of sets of written stage directions that encourage spontaneity and improvisation.

Cubase, Logic, Pro Tools, Digital Performer, and other digital audio workstations (DAW) enable a composer to collage on a timeline manipulated synthesized electroacoustic sounds, sampled analogue sounds, and virtual instruments (literally anything one can dream up can be introduced) on hundreds of tracks at a time. It’s a bit unwieldy, but you can even add notes by picking and clicking — the onscreen graphic result resembles a piano roll. Factoring in the ability to “play in” ideas on a midi-compatible instrument, the workspace is even more fluid and intuitive. It is a liberating creative space that, unless some sort of interaction with live performers requiring sheet music is required, requires of the composer no traditional musical notation skills. The onscreen display looks like a horizontal bar chart

The very first piece that I sketched on King Brand was Prayer for Peace, a string orchestra piece that ended up figuring prominently in my personal and professional narrative when in 1981 the Philadelphia Orchestra premiered it.

If fliers dream of flying, then composers dream of music. To presuppose even an array of black and white keys rather than a QWERTY keyboard (even that is a parochial presumption) is to forget that most commercially viable music is created at a DAW (Digital Audio Workstation) now and, rather than referring to it as “composing,” it is called simply “making music” as it may combine analogue and digital elements (notated, improvised, aleatoric and indeterminate all) and result in a realized performance in itself.

A primary appeal of DAW to some is that it enables one to create music without having mastered conventional western musical notation. One can “play the music in” on a digital piano keyboard or drag and drop “loops” (pre-packaged and self-created) into a timeline, and so forth. If analogue musicians are to be involved in the work’s performance, then a “MIDI dump” (Musical Instrument Digital Interface) of the music created in the DAW can be exported to a musical notation application like Sibelius and then “refined” by a human musician for use by performers.

Severe arthritis in my hands has made it frustrating to grip any writing utensil for long periods, and painful to play the piano, and my eyes aren’t what they once were, with the result that now I sketch a few thoughts on paper and compose everything away from the piano. If it is notation-based, I type the music directly into full score; if it is a floridly electroacoustic score, like Orson Rehearsed or 9/10: Love Before the Fall, I compose directly into Logic Pro. Whether I ever use it up or not, I have about 450 sheets of King Brand on a shelf next to my piano — enough, I murmur superstitiously to myself every time I tap the Baldwin’s case as I walk by, to write the next opera, if it comes.

New Beginnings

“Sonata” literally means “a piece played,” as opposed to “cantata,” which is “a piece sung.” “Opera,” in the original Latin, means “labor,” or “work.” Reddy blueys and Blackwings sharpened, light just so, eraser and treasured talismans to hand, it is time to consider “the next opera, if it comes.” Or opus, if you will. Or nothing, if you won’t.

So, the lock’s been picked, the interior has been revealed. The torrent is raging, and you’re hoping that in drawing from it a tiny cup of water you won’t get swept away and drowned. You’re simultaneously zooming into the zero during the first shot of The Matrix and Moon-watcher now, and the bone Kubrick gave you that you threw in the air has become an orbiting space station. The static has cleared, and you’re picking up, if only for an instant, a strong, clear signal. You’re hearing Franz Schreker’s ferne Klang, and, as John Donne reminds us, it tolls for thee, sweetheart: so get to work.

Creation. The act, not the activity. There is no right way to do it; but there truly is also no wrong way. It cannot be taught, cannot be forced. It is often accidental, always unique. It can be reflexive, like a sneeze, uncontrollable, like a breeze. It is undeserved, like love, and unearned, like grace.

Talent. The resource, not its utilization. Unbidden, unearned, easily mangled, squandered, and overlooked. Beyond understanding, it is immeasurable, uncontainable, and infinitely resilient. It, too, is unearned, a gift.

The activity and utilization of creation and talent is where everything gets mixed together with the humdrum dialectic between creation and destruction. The ego can’t help trying to cut the enormity of creativity and the creative act down to size, trying to put a saddle on it, trying to make creativity a commodity like real estate. Who hasn’t mused to themselves “what I lack in talent I will make up in hard work?” when the futility of clinging to Socrates’ distum that an unexamined life is not worth living becomes unbearable? Don’t forget that Socrates was sentenced to death.

Working Hard doesn’t necessarily improve the Work. Suffering is not a competitive sport; there’s plenty of misery to go around. Keep the academy at arm’s length. Artistic freedom requires more than self-actualization, which can be achieved through selfishness. True artistic freedom involves a broader quest for something larger than oneself: the transcendence of boundaries and the connection of people in a meaningful way. Choose your personal narrative wisely, young Padawan, and don’t let other people define you.

If you think older composers don’t treat you right, act in a way that you deem entitled, or behave like arrogant name droppers, ask yourself why you are allowing them to live rent free in your skull. Drop the Resentful Genius and Tortured Artist Rastignac schticks. It is your time! Just get your work done. Finish what you start. Once done, it doesn’t matter what you say about your music; it speaks for itself. Most likely everything you have to say has been said before, and better, just not by you, so have some humility and perspective on what you are doing. And, for Pete’s sake, put it out there, because it doesn’t exist until it is heard by others. If people don’t like your music, it isn’t their fault

At age 64, David Diamond perused an orchestra piece that I sent him when I was 16 called Kamala at the Riverbank and wrote to me, “As of now, I sense enormous facility, no interesting thematic ideas, and little self-criticism.” Paul McCartney wrote the tune When I’m Sixty-Four when he was 16. I realize now that some of the art songs I composed in my teens (published by E.C. Schirmer in 1983) before receiving a single composition lesson are some of the best, and most frequently-performed, of the over 300 I’ve penned. David was right, of course. And now he is dead, Paul McCartney is 83, and I am the one who is 64. That’s Life and Art for you.

How many budding composers’ creative voices have been mangled because the flowering bush of their imagination was pruned in the spring of their lives by the well-meaning mentorship of “experts” who, to be fair, can only teach what they know? Musical ideas are precious. What gives anyone the right to say when one is false? On the one hand, there is the purity of Rainer Maria Rilke’s famous admonition to a young artist that “nothing touches a work of art so little as words of criticism.” On the other hand, subtle musical minds with a profound sensitivity to the aesthetic are often the first spirit-manglers when they succumb to the temptation of throwing around subjective ideas like “taste” and “class,” “self-criticism”, “personal voice” and “originality.”

Abstract tunes that never soar do not necessarily fine art make. Penning memorable tunes is risky because, as soon as one takes wing, some people reflexively shoulder their rifles. Expect some colleagues to label your work then as “derivative” or “cheap, or “filmic.” Assess the feedback, but be mindful that some reactions can be driven by a sense of envy. Forgive their bitterness and get back to work. They lack the courage to choose clarity over cleverness, opting instead for “safe” choices blessed by their mentors. Remember: talent isn't a possession, it's a responsibility. Don't let their unearned authority stifle your devotion. Don’t let them shoot you down.

When she sculpted, my mother, I wrote in my memoir, “used me as her model because she needed a subject, she loved me, and because I was available.” It is as close as I have ever come to understanding how and why people choose their subjects, and the way they elect to express themselves. As I modeled for her as a child, she modeled me in clay while modeling the artist’s mien and methods. She sculpted what she knew, what she cared about, and what she had at hand. Most important, she liked doing it.

Because I am a composer, the rhythm and sound of the words in the previous paragraph tell me more about what the words are trying to express than the words themselves. Verbal rhetorical strategies are a square hole and my mind is a round peg. I am prone to tautological thinking, which is bad for spoken language but great for music. I’m good at logic and bad at math; I’m good at complexity but committed to simplicity. Instinct leads; intellect follows. While I don’t necessarily trust what I’m feeling right now, if I try to express it in words, I’ll fail; if I sing it, it will be true. Music makes people feel things whether the composer felt them or not. Dogs howl. Why not you? I could have said all that with five notes. And should have.

Keep it in Mind

Jeanette Ross, my piano teacher at the University of Wisconsin in Madison in fall 1980, had assigned me the Beethoven Piano Sonata No. 18 in E-flat Major, Op. 31 No. 3 because, she said, “it isn’t too hard and it is one of the best examples of sonata allegro form in the repertoire.” I loved her, and I loved how practicing Beethoven made me feel. When, of a Monday morning around nine I hied me to her studio, having made some meaningful progress. I had also just pulled an all-nighter copying the orchestral parts for my composition teacher Les Thimmig’s new Amethyst Remembrance and was myself composing a big orchestral blowout called Triptych. Unslept, right hand stiff from brandishing an Osmiroid fountain pen for the past ten hours, I had just enough time to warm up before the lesson. Coordination shot, brain fried, I played as best I could, eyes glued to the printed music, and twice rewrote several of the inner voices in the Menuetto. Gently stopping me, Dr. Ross didn’t admonish me. She asked, “How long is it since you last slept?” Then, “Are you aware that you’ve recomposed the inner voices?” I was not. She played me what I had done and then the correct way. I played it back correctly, saying, “I promise that I practiced it correctly.” “I believe you,” she answered. “These things are what make you a composer,” she said. “I’ll teach you as much as I can, but I know that your own music will always be leading you and requiring the best of you. Now go home and rest.”

In summer 1984, after having been composing steadily for about seven years, my preferred creative rhythm fell into place during a residency at Yaddo, the artist retreat in Saratoga Springs, New York. I was able then to reliably hold about three minutes of my own fully-imagined music in my mind before losing track of, or muddling up, the details. (This isn’t as unusual as a non-musician might think.) Beginning with breakfast and lots of coffee, I’d walk to the studio where, without distractions, I could get those three minutes “out of my head and on to paper” over the course of five to six hours. The time flew, the notes accumulated, and the intellectual outlay would wipe me out. At the end, I would feel like I was tripping on my own dopamine as I walked in a zoned-out, practically post-coital afterglow state back to my room, where I would change and go for a run around the ponds (during which the music I’d written down that day would cycle again and again through my mind) and get even higher on the endorphins unlocked by exercise. Most people unwound after dinner. I’d head back out to the studio to execute the less mentally taxing composer chores like copying out the “fair score” of the just-completed work and making minor, gentle revisions. Then, I’d stop, three or four measures before the point at which the music I had been holding in my memory and had notated on paper ran out. This lagniappe contained the musical threads that I would take up the next morning. An insomniac who had been on the lookout for sheep to count since my teens, I took comfort in the shuffling and reshuffling of musical ideas. The ensuing lucid dreams resulted in what I found then and still regard as miraculous and undeserved: waking up with the next stretch of music in my mind fully formed and accessible.

Four things: first, to each their own. I am aware that my way of working is no better or worse than anyone else’s: all that matters is that the music comes. Second, as a child alone at the piano, I had, because of family dynamics, developed the ability to concentrate despite nearly all distractions, including other musics, and through nearly any emotional distress. Third, bliss is in being able to be flexible and to evolve: having children taught me that one can as though by magic get twice as much done in half the time if one has sufficient skills. Fourth, the act of composing has always been a source of joy to me, despite and still — always.

Ouroboros

Fifteen-year-old me listening for the tumblers to click into place, poised on the verge of an insight. Ellie Arroway with her fingers poised over the tuning dial. The miracle of the word or the sound you were hoping to hear coming into your head when you ask for it. The instinct to pounce on and incorporate a better one when the imagination, without evidence or conscious reasoning, serves up something better.

The drive to develop the skills (whatever they are) required to remove the inevitable distortion and unwanted noise interfering with the pure, ferne Klang inside your head as you transfer it to the page through your heart, eyes, ears, arm, wrist, hand, pencil and then, zooming through the zero and emerging on the other side: off the page and into the mind of a performer who translates it into sound by way of execution through eyes, mind, heart, fingers, lips, breath, intuition, My God, the entire process is breathtaking. What were we talking about? What were we trying to express? Why does Bach’s B Minor Mass inspire such solace, such undeserved grace? How can one resist the temptation to find not the unbearable lightness of being but God’s mercy and forgiveness in such an awesome display?

Robbie’s final monologue in the screenplay for my operafilm I Hear America Singing begins: “The thing is, you put the work out there, you put everything you’ve got into it and then it lands and then — poof — it’s gone. And you learn that that is the way of things ….”

Quick and unpleasant trick question: did you just reflexively roll your eyes? Why does the call to feeling something constitute for some insufficiently self-critical, amusingly middlebrow, cheap sentimentality? Do you believe that some people’s tastes (compared to your own, of course) are truly more refined, their cultural reference points more elevated, their educations more elite, their relative authenticity better established, their social expectations deserved, their sense of entitlement unquestionable than your own? “Who are you to refuse my sugar?” bellows Komarovsky at Lara in Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago, “Who are you to refuse me anything?”

Revere great work and great talent for the natural resources and awe-inspiring examples that they are and then get over yourself and concentrate on the work. Stop measuring yourself against others. Accept and find a way to deal with the fact that others will judge you and your work. Other artists can give you advice about how to do this. They can’t help themselves.

The creative act is one of love, of faith in the importance of individual conscience, the importance of having the courage not just to be oneself but to accept others as they are, to not sing so loudly that you’re drowning out other peoples’ voices. Countless times over the past forty years I have heard myself say “be brave” to a pupil or colleague, or myself, knowing that, as F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote to his daughter Scottie in 1940, “Life is essentially a cheat and its conditions are those of defeat,” with a chaser of Witold Lutosławski’s comment in Evian to me about my music when he was 69 and I was 21: “It’s all you, of course; it’s all you. How could it not be? Be young. Write like this. Write. Create. Or the Bad Guys Win.”

Finish it. Share it.

Take all the rejection, hurt, pain, and misfortune my children (my heart outside of my body) are bound to receive during their lifetimes and roll it into one toxic pill and you’ve got the dread that I feel when I share a new piece. I know that I can’t protect my children, that I’ve done everything that I can do to prepare them, but that sometimes the reception is just going to suck. Some people will hate them for unfathomable reasons; they will have done to them and do to others and themselves unfixable damage. But they will also find love, and wonder, and do good, and feel awe, and acquire wisdom, move others and be moved.

Having emptied the safe, passed along the transmission, you allow the door to swing gently shut, the signal to fade. You’ll let them grow up and leave you, watch them gallop off in the wrong direction without crying foul. Your piece will become a treasured talisman to a few, an unopened book on a soon-to-be razed library shelf to others, and utterly non-existent to the other 99 percent of the world. You’ll release your memoirs to the sound of crickets, become the lock of mane in a musician’s violin case, and once in a while, you’ll wonder for a moment how the hell that thing you composed touched so many people. It was never about you.

Begin again.