When Thornton Wilder’s 1938 meta-theatrical triptych of portraits of American Life Our Town (which, no matter when it is staged, always takes place in 1938) was produced at the McCarter Theater in Princeton, twenty years had passed since the American Dream had been convulsed by the “War to End all War.” That which burns away any Rockwell-esque nostalgia and powers the drama of the play is the “Damoclesian sword” that was the rise of fascism and the impending outbreak of World War II—only months away. The audience was invited to grieve for the characters from the moment that they met the omniscient, fourth-wall-piercing character of the Stage Manager. It was in the air: Marc Blitzstein’s The Cradle Will Rock, (with Blitzstein and Orson Welles on stage essentially splitting the role that Wilder would transform into the Stage Manager for his Our Town) had electrified the American theater during summer 1937. Louise Talma (the only composer besides Hindemith to convince Wilder to pen a libretto, in German, no less—for her earnest, turgid Alcestiad—in the ’50s) told me at Yaddo during the ’90s that “Thornton certainly knew Marc’s opera. The Depression was winding down. We saw Hitler coming to power. People were mourning Good Old Days that never were.”[1]

Arguably, Wilder’s “continual dryness of tone”—as he described it in the introductory note to the 1938 “acting edition” of the play—found its ideal composer in Aaron Copland’s seminal 1940 musical score (dedicated to Leonard Bernstein) for the original film.[2] Copland, according to Vivian Perlis, stated, “For the film version, they were counting on the music to translate the transcendental aspects of the story. I tried for clean and clear sounds and in general used straightforward harmonies and rhythms that would project the serenity and sense of security of the story.” Rudolf Bing, then general manager of the Metropolitan Opera, approached Copland in 1951 with the idea of expanding his score into a full-length operatic version. Wilder, according to Perlis, quashed the idea, responding, “my texts ‘swear at’ music; they’re after totally different effects.”[3] What was required, as Wilder wrote in his introduction to the play was, “the New England understatement of sentiment, of surprise, of tragedy. A shyness about emotion ... a sharpening and distinctness of the voice.”

Fast forward. Wilder said no to many composers during his lifetime, though he did permit Jerry Herman and Michael Stewart to turn The Matchmaker into Hello Dolly and, in 1965, did grant rights to Leonard Bernstein, Betty Comden, and Adolph Green to adapt The Skin of Our Teeth into a musical. Musical theater collaborations are fickle—everything’s got to fall into place or the producers bolt and the soufflé falls. Everything didn’t, and the project collapsed. When Lenny returned to Wilder, seeking operatic rights, Wilder shut him down. We are the poorer for his decision.[4]

I studied with composer Ned Rorem during the early ’80s while a student at the Curtis Institute, and served as his copyist for half a decade after that. I knew his music from the inside out, and I knew particularly well his short operas. Art song composer nonpareil, he and Kenward Elmslie had adapted August Strindberg’s Miss Julie in 1965 with mixed success, and many thought him not suited to the demands of large-scale lyric theater. But Ned persevered, and garnered universal praise from opera stalwarts when, in 1994, he returned to Miss Julie, trimming it into a “taut and persuasive” 90-minute one act, according to James Oestreich in the Times.[5]

J.D. (Sandy) McClatchy, the svelte poet, erudite editor, and versatile librettist for Little Nemo in Slumberland (Daron Hagen), Miss Lonelyhearts (Lowell Liebermann), 1984 (Lorin Maazel), Dolores Claiborne (Tobias Picker), and A Question of Taste (William Schuman) among others, and I met when translator William Weaver commissioned me to compose some songs in memory of James Merrill—Sandy was Merrill’s executor. I admired his libretti and told him so. He said that Tappan Wilder had agreed to loosen the bonds on the Our Town rights, and that he, Sandy, was looking for the right composer. How, he asked me, would I proceed if I took on the job? I don’t recall now what I said, but I do recall ending the conversation by saying, “You know, the man you’re looking for is really Ned Rorem. Ned’s Quakerism provides the proper emotional repose; his age the appropriate cultural reference points. Most importantly, he’s entirely secure in his own voice, and will be comfortable letting Wilder’s play take the lead.”

I doubt that Sandy chose Ned because of what I said, but I knew then (and now) that I was right.Our Town the opera was premiered by Indiana University Opera Theater with student singers and orchestra on February 25, 2006. Its professional debut was at the Lake George Opera on July 1, 2006. Intended from the start to be a chamber opera, the orchestration is small, and the scoring is light and transparent throughout—consistent with a work best suited to young voices. The formal structure follows Wilder’s play closely. Minor deviations from the original play seem to have been made (the fleshing out of the role of Simon Stimson, the creation of choral numbers, for example) to provide opportunities for musicalization. Rorem moves in and out of speech and utilizes more elevated recitative (parlando) than in his previous theatrical works.

Playing through Ned’s first manuscript vocal score with Gilda Lyons shortly after he finished his first draft, we pounced upon the opportunity of giving the concert première of the (now classic) aria for Emily. (Notably, the opera’s only freestanding set piece.) In it, the ironic union of opposites that make the opera Our Town the immediate American classic that it is were on full display—economy of construction, absolute, unwavering resistance to unnecessary emotionalism, frankly open textures, wisps of Poulenc at his driest, and the sort of stunning Protestant hymns that only an atheistic alcoholic Quaker whose life partner was a church organist can pen. Everywhere in the music there is a sort of cool, self-contained regretfulness—the regret so central to the play’s initial impetus, a regret so intense as to border on dread—that perfectly underpins and undercuts the sentimentality of the portraits.

Rorem uses three compositional strategies to hold the opera together structurally, track the story’s narrative, and to keep his musical rhetoric coherent.

First, he manifests Wilder’s “emotional shyness” with abrupt stylistic cross-cutting (in mid- thought, sometimes in mid-musical phrase) between Americana (Thomsonian faux-Protestant hymns, plush sustained cinematic strings, Copland-esque woodwind solos, Ivesian collages), transatlantic modernism (the tartly-scored “sting” chords, jagged, off-kilter ostinatos in close- canon, denatured melodic fragments in place of memorable tunes), and Gallic lyricism (rapturous string obbligatos, sudden snatches of emotionally-vibrant melody, Debussy-esque orchestration).

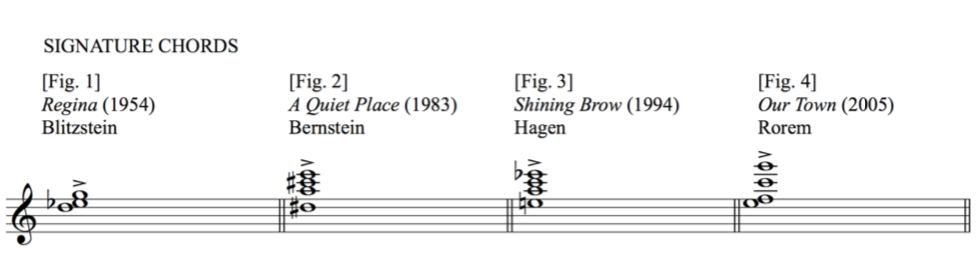

The first sixty seconds of the opera deftly arrays all three techniques. The pungent bell-tone chord that strikes 5AM declares that Our Town is part of a continuum of American operas that frankly destabilize traditional harmony by thrusting, like a billy to the ribs, an unresolved fourth into the triad. Blitzstein’s poisoned capitalists, Bernstein’s tragic suburbanites, my tormented architect, and Rorem’s dread-filled citizens of Grover’s Corners all inhabit the same American operatic landscape. Ned immediately crosscuts to another of his favorite tropes—the faux Protestant chorus underpinned harmonically by parallel unresolved sevenths in the bass—before overlaying a sudden, Gallic, sensually-arresting obbligato in the high strings. When the action begins, the parlando (passages of elevated speech that do not quite rise to song) section that follows is typical of the handling of dialogue throughout the opera: The characters unpretentiously skitter halfway between speech and recitative over a plush, comforting pad of sustained, Copland-esque strings.

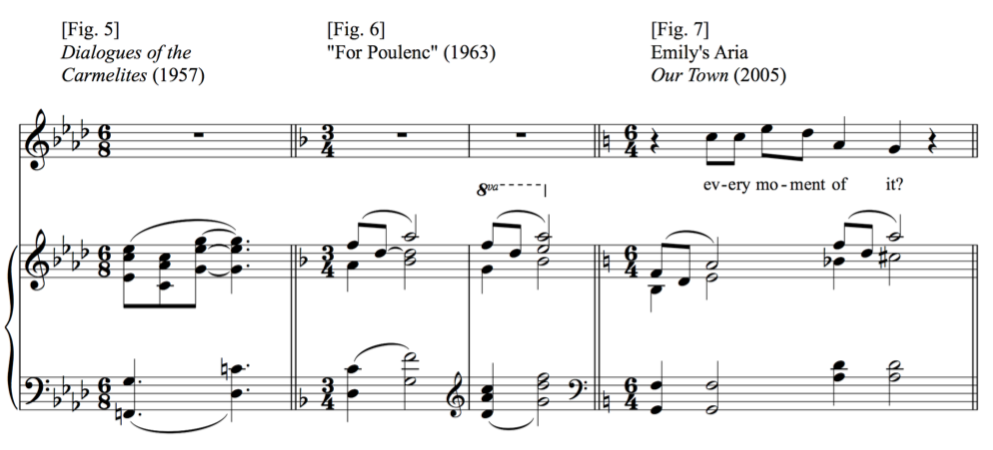

Second, throughout the opera, beginning in the background during the first moments as a woodwind obbligato like a nettlesome foreigner, is a “deedle-dum” figure that unmistakably evokes the falling motif associated with the doomed nuns in Poulenc’s Dialogues of the Carmelites[Fig. 5]. Rorem’s personal association with the motif inspired him to quote it in his own song, “For Poulenc” [Fig. 6], and, over the years, a dozen instrumental works, large and small. In the score of Our Town, it completes its transit (in Ned’s life as a composer and in his catalogue) in his characterization of Emily [Fig. 7].

The motif evolves inexorably over the course of the opera, generating tension the way that someone playing with their hair during a serious conversation is at first slightly distracting and, over time, enervating. It begins to take on a life of its own as the second act unfolds, the curling of melodies in the background behind the characters’ parlando turning in on themselves in an Ouroborus-like way, transforming the fragments into slowly unraveling ostinati that are both claustrophobic and comforting—like the family life Rorem’s music limns. Characters begin taking on the background ostinati and incorporating them into their parlando in odd melismatic passages that heighten words in a baroque fashion. As the second act closes and the young couple marry, the dread given us by the first acerbic chord of the opera returns, literally underscoring the fragility of their happiness. A violin solo gives another fleeting taste of sensual pleasure before Rorem snuffs it as, again, “too much” to close with an anything but comforting, dread-filled, Ives-ian mash-up of the “Mendelssohn Wedding March.”

Pedal points in the strings, quizzical quasi-chorales in the winds and brass, the “deedle-dum” curling wind obbligati, all return in the third act; the opera continues to unfold, but all the vocal lines are heightened above parlando (they’re taken closer to “song” and effusive tunefulness by making their tunes less abstract and more traditionally singable and giving the phrases more melismas) in a way that they weren’t in the first two acts. This “gradual emotional warming” manifests Ned’s third, and most subtle, strategy for giving the opera emotional depth, the character of Emily emotional verifiability, and the piece a satisfying emotional trajectory.

This is how he did it. Gradually, Rorem invests the chorus with more and more emotional warmth so that they—in death, but not in life—create the sort of musico-emotional landscape into which Emily can step. The apotheosis of the opera is, of course, Emily’s aria, wherein Rorem combines at proximity all the musical gestures laid out in the first two acts. In this, the “eleven o’clock” spot, he gives Emily the only unabashedly rapturous music in the opera, and on the most regretful sentiment: “Do any human beings ever realize life while they live it—every, every minute?” The composer’s self-control in finally allowing us to “feel” is masterful; the effect is devastating. His obvious identification with Emily, Poulenc, and the nuns is an astonishing personal revelation for a composer so famously public in his prose and yet so resolutely private in fact. Emily concludes, as Ned (a writer who eschews exclamation points and composer who famously hates repeating words, breaks his own rules) sums up a world-view, “That’s all human beings are. Blind!”

But why did Our Town need to be made into an opera? Just 80 years have elapsed since the 1937 premiere of Wilder’s play, yet a 1938 audience’s dread is like that felt in many quarters in 2017. Spring 2017 may find Americans in greater need of the sort of narrative that Our Town provides than they have been since the ’30s. The “Damoclesian sword” of rising fascism has returned with a vengeance; we’re told that we’re not experiencing a Depression, yet unemployment isn’t being measured in a way that considers how many people have simply stopped looking for work, or the fact that retired people are working at Walmart to supplement their pensions. The Peterborough, New Hampshire, that Wilder used as a model for Grover’s Corners had faded to the margins by the time I began visiting the MacDowell Colony during the early ’80s. Nobody in Wilder’s play could afford to live in the Peterborough of today.

Ned has told me that Satie’s Socrate may be “the greatest of all operas.” Certainly, he exploits in his score for Our Town the same kind of baroque cantata textures and affects as Satie did in his 1920 masterpiece and that Wilder (according to Mabel Dodge)[6] most preferred. But the Rorem and McClatchy Our Town also contains—in the propulsive, off-kilter ostinati percolating uneasily beneath the Nantucket matter-of-factness of its musical surfaces and its stubborn unwillingness to wear its heart on its sleeve—an astonishing undercurrent of unanticipated, and highly effective dramaturgical fury.

This article originally appeared as the liner notes to New World Records 80790-2 [2 CDS] world premiere recording of Ned Rorem and J.D. McClatchy’s opera Our Town, based on the play by Thornton Wilder.

Footnotes

Louise Talma in conversation with the author at Yaddo, summer 1995.

Thornton Wilder’s “Some Suggestions for the Director” from the 1938 “acting edition” of the script.

Vivian Perlis quotes Aaron Copland in a letter to the New York Times, January 31, 1998.

Tappan Wilder, program notes for “Thornton Wilder and Music,” a program by the American Symphony Orchestra, December 19, 2014.

James Oestreich, New York Times review of the Manhattan School of Music production of the revised Miss Julie, spring 1994.

Mabel Dodge is quoted by Tappan Wilder in his American Symphony Orchestra program note.