Beginnings

A prepubescent boy of 12 bathed in dazzling stage lights in 1973 sings Norman Dello Joio’s 1948 setting There is a Lady Sweet and Kind accompanied at the piano by his fearsome teacher, a man named Wallace Tomchek, at some rural high school in Wisconsin for three non-descript oldsters checking off boxes without looking up until the end when it is revealed that one is weeping.

In the beginning, performance is what you make of it. In the end, when you finally become what a lifetime of performing has made of you, you’ve become a means of transmission, an instrument. In between comes the performing. And the bear. More about the bear later.

Public Performing: the ritual for which one dresses up (or not) in concert blacks, hits the deck, and participates as performer or auditor in a transformative exercise facilitated by music-making, is undeniably an opportunity to enjoy and explore peak human and aesthetic experiences that, in their rightness, touch peoples’ souls and enrich their lives.

Christmas 1978, as a tenor in the choir during a recording session of, among other seasonal pieces, Holst’s Lullay My Liking I am moved to secret tears of gratitude and joy by the sudden, staggering understanding of how very much I love all the people with whom I am singing, that we are good and that, no matter where everyone’s paths will take them after graduation, we can take gentle, youthful pride in our performances; that our conductor Kay is excellent, and that she and Tomchek have taught us well; that this is a memory, a peak moment, if I can hold on to it, an instant that, if correctly remembered and left unadorned, might help carry me into the future.

Listening to the recording just now, I can still identify individual voices in that long ago chorus, and I am transported in time to who I was then, able to examine the skein of memories that ties the man I am and the boy I was in a way that consoles and admonishes, celebrates and memorializes. Memory is what makes us human; it is the Madeleine. But it is performance that activates memory and compels us to act.

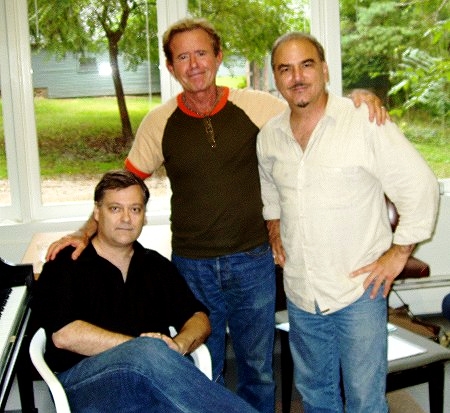

Private Performing: composer (and former chef) Carlos Jaquez Gonzalez observed to me during filming of the operafilm 9/10: Love Before the Fall (in which he sang the role of Tony) how alike Family Meal in the restaurant world, chamber music with friends, and ensemble building in the theater are. I have leaned into that with my New Mercury Collective.

I am with stolid deliberation working my way through a new French language edition of Marcel Proust’s À la recherché du temps perdu — a gift from the Camargo Foundation’s resident director, Michael Pretina — side by side with my mother’s nicotine-stained 1934 English language edition. It is November 1989. The Mistral is marching stiffly down the Alps and sweeping across the Côte d’Azur on its way to North Africa, so I am wrapped in jeans and a shocking pink woolen Benetton sweater purchased a few weeks earlier in Venice with money I don’t really have and in which I have sweated. It still looks good, but it smells a little funky. A few days earlier I had set Paul Muldoon’s poem Holy Thursday to music, and have volunteered to perform it, along with a few other songs—some Barber, Rorem, Bernstein, and a couple of my own—at a soiree Michael is throwing for some donors. I can hear the rhythmic crashing of the waves on the limestone cliffs below the villa and, on a lark, synchronize to them the thrumming chords of the piano part of my setting of Paul’s poem. As I play for an instant I realize the moment for what it is.

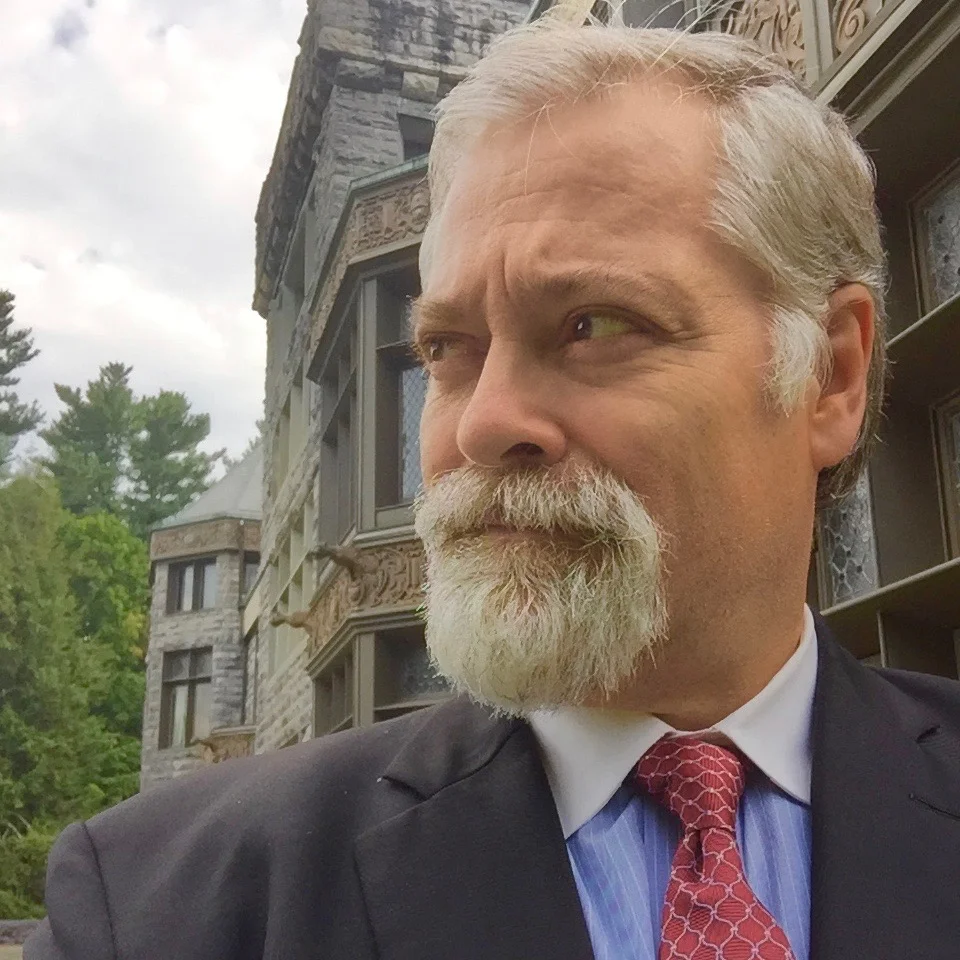

The riskiest performing of all, the ultimate gift that performers can offer one another, is the sharing of unfinished drafts or unpolished performances. Complete trust and inclusion of others in one’s creative space. As a composer who performs, mine is the music room at Yaddo, the artist retreat in Saratoga Springs, New York.

Sitting next to David Del Tredici, giddily charging through Mozart Symphonies four handed arms like spaghetti on a summer afternoon in the early 90s; David accompanying me as I roughhouse my way through Now You Know — a song with words by Antler and dedicated to me about, among other things, how male babies in the womb get erections, and how many, and how often — to a roaring audience of guests in summer 1998; David’s exquisite accompaniment as I sing my setting of Gardner McFall’s Amelia’s Song in September 2005 for the rest of the guests after dinner while composing the opera; accompanying Gilda Lyons myself in my arrangement of the hymn Angel Band before dinner during an annual board meeting sometime during the aughts; weeping, a few days after Ray Charles’ death in 2004, while singing and playing my setting of Stephen Dunn’s Elegy for Ray Charles (were Stephen or David aware yet that they had Parkinson’s?) for him in the middle of the night.

I may have thought that I was a pianist, singer, or conductor before I landed in conservatory, but that nonsense was knocked out of me the first time I walked down the second-floor hallway at Curtis lined with the sepia-colored group graduation photos (of Gary Graffman, Jorge Bolet, Leonard Rose, Jaime Laredo and…) to the sound of kids younger than me crushing repertoire that I’d never have the technique to perform. From that moment on, I thought of myself as “a composer who plays the piano,” despite all the piano lessons and some really terrific teachers, with whom I am grateful to have studied — beginning at 7 with a stern Polish Holocaust survivor named Adam Klescewski; then Duane Dishaw at the Wisconsin Conservatory of Music; and then Jeannette Ross at the University of Wisconsin; ending with Marion Zarzeczna, a pupil of Horszowski’s, at Curtis, who taught me finally how to not play “like a composer.”

Just as composing requires a safe, secure space from whence to create, performing requires that you feel safe onstage. Every one of my teachers observed with wonder how comfortable and at ease I was at the keyboard. It was because, when I was fifteen my mother made my father promise that, if I were at the piano, then he could not summon me to perform any of the numerous random tasks that he demanded of all three of his sons when he was home in what we decided was a conscious desire to keep us from relaxing. For me, the result was that the moment I took to the bench I felt safe. In performance, charged with lifting up and protecting a singer, I was always and have remained, entirely in command of myself as a performer because I’m not there for me: I am a man on a mission.

I made the most of the technique that I had. I performed on hundreds of concerts as a collaborative pianist, made records, coached, and put over from the piano a dozen operas to collaborators, producers, and colleagues. I’ve always acknowledged my place. After hearing me premiere some songs with Douglas Hines, Vladimir Sokoloff told me, “You’re a fine collaborative pianist. Soloist not so much.” I am grateful for that.

Middles

Putting over Frank Lloyd Wright’s “Balsam fir” aria from Shining Brow for Lenny on his beautiful Baldwin at the Dakota in 1990, knowing it was good stuff; the absolute I-can’t-believe-this-is-happening thrill of hearing him channel my compositional voice and manipulate it without corrupting it, singing and playing through the same material in his gravelly-schmoozy voice, and by doing so, teaching.

A colleague once turned to me just before I was about to perform on a benefit concert at Alice Tully Hall and groaned, “Please just don’t play like a composer, okay?” I have encouraged dozens of proteges over the years to perform their own music so that they will learn this tough lesson firsthand. Accustomed to filling in the blanks, focused on the larger musical argument, composers typically forgive themselves for their technical inadequacies. When we compose at our instrument, we hear the music we are making as it ought to sound instead of the way we are playing it.

“Playing like a composer” is one thing. Among serious composers and pianists both there is a stigma attached to the ability to “put a song over” at the keyboard — what composer Tevi Eber reminds me is dismissed as playing like a “theater pianist.” It happens that I am very good at it, though I stopped doing it when arthritis made performing more painful than it was worth. When he first landed in New York City in the early 40s, Leonard Bernstein did some work arranging, transcribing, and notating jazz improvisations for Harms under the pseudonym Lenny Amber. (I did the same thing, for another publisher, during the late 80s.) Distancing oneself from “hack work” is one thing, but LB was (besides being a terrific soloist) a super-practical musician, and proud of the fact that he could “put over” his shows “the way that Marc [Blitzstein] did” and function as a first-rank professional performer.

Afternoons every couple of months with Paul Sperry over the years in his studio at the Majestic on Central Park West in New York City reading through the stacks of song cycles that composers sent him, enjoying the adventure, the challenge, the overview of what was happening in the art song world, the bits of wisdom imparted, the thumbnail critiques of the vocal writing, the laughter, the wine, quite simply … the playing.

Concert music composers often bring unexpected, fascinating, and enchanting aspects of the music they perform in public — particularly their own. One legitimately wonders whether or not their performance is somehow more authentic. (“I meant those wrong notes.”) Setting aside commercial issues like when musicians are compelled to “cover” their own songs the same way every time to "preserve the brand,” the conventions of pop music allow us to enjoy composer Paul McCartney’s teenage demo performance of When I’m Sixty-Four and a performance he gives of the song at the age of … sixty-four equally.

Procedural memory is a crucial aspect of being an effective performer. That’s why one practices scales, which, aside from keeping one physically limber (more about that later), create a wealth of repetitive motions that can be executed without conscious management, increasing suppleness of execution, improving one’s technical precision, and even storing history itself in the retained motor skills.

Teachers transfer their muscle memory to their students by passing along to them their personal fingerings. This practical aspect of the oral tradition has a lot of history and poetry to it. Consider that Tchaikovsky was assisted by his composition student Iosef Kotek (a violinist) who provided practical advice that helped his teacher make the solo part more idiomatic. Tchaikovsky offered the piece to Leopold Auer, who rejected it (a ding the piece had to overcome in order to get legs), so the premiere went to Adolph Brodsky; but then Auer picked it up later and passed along his fingerings and interpretation to his students — Elman, Heifetz, Milstein, Shumsky, and Zimbalist, among others.

Concert musicians are typically unforgiving of “wrong notes” mainly because playing all the “right” ones is at least empirically provable (“He can play all the notes in Brahms, but he doesn’t understand him,” I once heard a cruel violist quip) and someone’s got to play them. Because immaculate technicians who play consistently need to exist in order to feed the musical ecosystem in which orchestras function more than inspired ones who play “wrong” notes, the best string players at conservatory often sit at the back desks. (And why every concerto competition has an etude round to eliminate competitors.) This was pointed out to me in April 1983 when, as students in Philadelphia, my girlfriend and I heard Vladimir Horowitz in recital at the Academy of Music. Age and wisdom rendered moot the issue of “wrong notes.” The colors, the artistry, the vision of his performing were mind-blowing. Notes be damned.

Hmmmm, that’s nice. No wonder the celli sound so plump there, I muse, hearing a bass clarinet doubling hitherto buried in the orchestration. Looking and sounding good during a rehearsal of Gershwin’s I Got Rhythm Variations with JoAnn Falletta and the Denver Chamber Orchestra in 1987, I’ve relaxed just enough during some passagework to let my mind wander. Up I go, my fingers rattling on by muscle memory, hearing things I’m not supposed to be hearing because I am not listening to myself. Even in the moment I am thinking “this is so cool” until I notice JoAnn glancing at me and I plunge back down into my own brain.

In the operafilm I Hear America Singing I have the composer wonder, “Where do people go when they go ‘up?’ Is it heaven?” If the moment of silence between the final sound and the first clap is where the bear lives (more about him later), then I think that the spirit of whomever composed the piece might live “up there,” with angels like Wenders’ Damien and Cassiel, observing and remembering. That’s why I’ve never “gone up” while performing my own music. If I ever do go up playing my own music, who will I meet there?

Just as there is a strict protocol governing the relationship between choreographer and dancers, there is an etiquette associated with composer-virtuoso soloist interactions that respects the roles to protect the people. Nearly every one of the soloists for whom I’ve written came to the first orchestra rehearsal with their part memorized. My job was to stay out of the way. Respecting the process, whatever their reservations, is their honor as a musician, just as it is the composer’s honor to give the work created for the soloist everything they’ve got.

Ideally, the soloist knows the piece so well that they take “ownership” of it, perform it as though they had themselves written it, in front of the composer, who actually knows when they are not hitting their mark. You can’t bullshit the composer, if the composer is the real deal. The soloist must lift up and protect from the bear not just the music but the composer by serving as an avatar, advocate, and champion. Accordingly, protocol dictates that the composer does not have the right to tell the soloist that they are not cutting it. Everyone knows that it is offensive to the paying audience, one’s colleagues, and to music for either the soloist or composer to think of, worse use, an engagement with one orchestra to workshop one’s performance before an appearance with another orchestra. What’s more, the soloist — whose fee to play the piece probably exceeds the composer’s fee to have written it — must responsibly and respectfully navigate a Green Room and dinner after with the donor, orchestra manager, and conductor.

In no other genre of concert music composing and performing do so-called “high art” conventions and expectations of the past so brutally collide (thereby exposing poseurs) with contemporary performance expectations. A concerto presented as an amicable exchange between equals sounds lovely, but the audience came for a bullfight. (Oscar Levant, in Humoresque: “A concerto is a contest between a solo instrument and an orchestra, in which the solo instrument always wins.") It is one thing to “put a score over” to give an idea of what the piece will sound like in the hands of a performer; it is quite another to accept a soloist’s fee and then to poorly perform one’s own or another composer’s work in a professional setting. The former is woodshedding; the latter is an unforgivable betrayal of not just the audience’s and the composer’s trust, but the conventions and history of the composer-soloist relationship.

After the premiere, much depends on how the premiere goes, and how people came to be hired. If the soloist initiated the commission, or is famous enough and likes the piece, they will then presumably tour with it. Management isn’t necessarily thrilled with this, because it is the point when the soloist is putting their reputation on the line for the concerto. That’s truly when one finds out of the piece has legs.

Orson Welles captures perfectly the effect that performing the same piece in different venues and for different audiences either on tour or over the span of decades feels like to me in the funhouse mirror sequence of The Lady from Shanghai. “Of course, killing you is killing myself,” says Everett Sloane, aiming his pistol at Rita Hayworth, who he sees in reflection with her gun aimed at him, along with his own face. “It’s the same thing. But, you know, I’m pretty tired of both of us.” Every shot that rings out causes another reflected version of Sloane, Welles, and Hayworth to shatter into a million pieces.

I’ve had this experience in my own small way with songs like Holy Thursday, which I’ve played, sung and accompanied hundreds of times in different situations. I am fascinated by (because I can’t imagine how) Anne-Sophie Mutter or Joshua Bell feel performing the Beethoven Violin Concerto in the hundredth city, or Paul McCartney performing Hey Jude, but I’d make an operafilm about it in a hot New York minute.

Ends

Because I came to music first as a singer — that prepubescent boy of 12 bathed in dazzling stage lights in 1973 — I’ve always been entirely at ease as a choral conductor. Hartzell, Tomchek, and Robert Fountain were excellent role models, and I’d been doing it without effort for years by the time Louis Karchin engaged me as his assistant with the Washington Square Chorus at New York University (an interesting bunch comprised of NYU students and community members) during the late 80s and early 90s. When I took over as music director, we had a run of several years during which I joyously deepened my appreciation and love of exploring the rapturously singable part writing of Monteverdi and Gesualdo by teaching them, week after week; picking up the stick to conduct Mozart — all the great repertoire I had been gifted to sing growing up.

Like most composers, I’ve been called upon to serve as conductor for various reasons, with ensembles large and small, fairly often over the years. I had excellent teachers: Catherine Comet was both terrifying and inspiring; and the help that I got from Lukas made me a respectable technician. Because I’ve only conducted when I needed to, I cannot in good conscience consider myself a conductor.

Stepping off the podium in Milwaukee and shaking the concertmaster’s hand after conducting Suite for a Lonely City— music that, via Bernstein, landed me on the east coast — in 1978 and intuiting that it was the beginning of something; bowing to Norman’s grieving parents in the little balcony in Curtis Hall after conducting the one and only performance of the memorial symphony I wrote for Norman in 1983, crushingly aware of the callow impertinence of my gesture; the feeling of disenchanted vindication I had when stepping off the podium in Las Vegas after having gotten my opera Bandanna in the can in 2000; thirty-eight years after looking down into the faces of my teenage contemporaries and feeling atop Mount Pisgah at the beginning of my story in Milwaukee, leading my fifty-something contemporaries and Gilda Lyons — in music that Bernstein once wrote as a young man for Tourel — on my birthday in 2016 in Philadelphia, relieved that it would probably be my last time on the podium.

Once Tin Pan Alley gave way to broadcast pop, songs usually ended by repeating the chorus or the hook while the music faded out, facilitating crossfades on the radio and enabling the band to improvise solos on the “ride out.” Odd how songs just end again in the Internet era. Most importantly, fade outs avoided the dreaded “full stop.” Full stops are downers. Full. Stop. See what I mean?

Transitions are where development and drama happen. Anybody who spins a narrative on some sort of timeline fusses with the transitions between set pieces, the reasoning being that, if you allow an audience to applaud, they’ve been released from the moment and must be pulled back in and their disbelief resuspended. “Exit, pursued by a bear” — the all-time greatest stage direction.

Concert music generally comes to a full stop (either it ends “up” or “down”) when the piece is finished. As a performer one hopes to have been so much in the moment that one’s behavior at the double bar is too crass a thing to consider, just as composers suppose — correctly or not — that the audience will be moved to reflect on what has just transpired and that their anticipation of the opportunity to express their appreciation will mount during whatever silence follows the last note. In that space lives the bear.

Seated at the piano in Curtis Hall in Philadelphia in April 1984, finishing the world premiere of a big song cycle called Three Silent Things, the performance of which would mark my last appearance as a student on that stage, looking up from my finger on the A key as the pitch decayed first at Rob’s face, hearing the B of his cello, then at Lisa’s face, hearing the D of her viola, and then Michaela’s as she held the F# on her violin, and finally at Karen as she sang, “this shallow spectacle, this sense,” on the tonic, I understood for the first time that Wallace Stevens’ poem A Clear Day and No Memories, which I had read as an elegiac, innig meditation on mortality, was in fact a clinical description of existential emptiness, the loss of love, and the end of memory. After I nodded the final cutoff of that simple Gmaj9#7 chord, it felt as though the silence that followed stretched on and on. I hadn’t until that moment had the conscious self-awareness to accept that we were all basically quits, and that, although our narratives would of course continue, they would diasporate.

At that moment, I was eaten by the bear. I was genuinely unprepared for the emptiness, the sense of loss, of, well, what Karen had just been singing about, to feel so viscerally awful. In this place a performer hears not one beat of applause, one word of congratulations; feels not one hug, smells not a single flower in the bouquet that has appeared in one’s hands. Stage Managers are the caretakers of this liminal space, guiding otherwise capable people past the bear and into and out of the wings, gently but firmly telling them to walk slowly or to rush. The bear has a huge repertoire: the imposter syndrome, performance anxiety, the fear of being deemed unworthy, judged, all the feels; for some performers, the hardest part is never having come to terms with the fact that there will never be enough applause, and that the Real World is still out there past the bear, waiting.

Making myself as small as I can at the piano in Philadelphia, sometime in fall 1982, I am aware that I am not here to perform, but to witness. Periodically, I am called upon to play a few measures of accompaniment, but otherwise I am superfluous. I try to commit to memory everything that Szymon Goldberg is saying to my violinist friend during her lesson. He isn’t just passing along fingerings, bowing, style, bow speed and pressure, and tradition, he is summoning the aesthetic world in which Debussy lived for her and gently referencing for her the way that a half dozen other great violinists have played the piece — some for Debussy himself — so that, as she commits the great Sonata in G minor to memory she will inscribe it in her own poetic memory. As she puts her violin to her neck, the spirits of Gaston Poulet, who premiered it, David Oistrakh, who recorded it, and more join her.

“The Germans were advancing on Paris,” I recall Goldberg observing, “and you can feel the end of the world in it.” Like Messiaen’s Quatuor pour la fin du Temps, the Debussy Sonata captures in music some essential quorum of understanding of the actuality of the end of time. Even in my early 20s I appreciated the coolness of her hand in mine as we walked home together that fall evening, and how superficial my grasp of Debussy’s last piece was. Understanding it would require a lifetime of study and experience. “To think he died only a few months after writing it,” she mused. “But he left us some breadcrumbs at least,” I replied.

Ned and I have finished a couple of games of backgammon at the red dining room table in January 1999 the day after Jim died and I say, “I’ll throw together something to eat” and he pushes the board away, saying, “I’m going to play something.” His retreating back. I move to the kitchen. When I hear him playing and singing a Hoagy Carmichael song in the living room, I stop what I’m doing, bow my head, weep stupidly, and listen.

Performing is praying, lullay-ing, baying, and kyrie-ing. Sometimes it even involves playing. In the beginning there is the swaddling band and the infant’s reflexive whimper; then, the Whitmanesque song of oneself; at the end there is the winding sheet and the survivor’s keen. Or is it the other way around? William Blake’s “piping, loud” arrival; Dylan Thomas’ raging “against the dying of the light;” T.S. Eliot’s ending “with a whimper.” In the end, when you’ve finally become what a lifetime of performing has made of you, you’ve become a means of transmission, an instrument.

Thanksgiving 2017, I tease out the first few notes of Copland’s dignified, soulful setting of the great hymn Shall We Gather at the River, look up at my partner Gilda Lyons and wait, contentedly, for her to begin. She raises her hand slightly as she often does when she begins a song. I think of the countless times I’ve held that hand; I think about the anticipation of restoration, and how her love and acceptance has transformed my sorrows into joys. Together we perform.