FCM: Let us go back to the beginning. What made you fall in love with cinema? How did you start making films and where did you learn how to make films?

DH: I fell in love with cinema because of my father, with whom I used to watch old black and white movies—the Late Show, and then the Late, Late Show—on broadcast television in Wisconsin when I was a child during the early 70s. I still remember—having fallen asleep during the second feature—waking up to the hiss of white noise and the eerie bullseye of the wavering test pattern in the dark and being led to bed. This was before videotape recorders were commercially available. Father mounted a jack on the back of the television and recorded the soundtracks on to cassette tapes, which I’d listen to over and over again, like radio dramas.

At 16, “learner’s permit” in hand, I began driving into Milwaukee from the suburbs with my friends to the magnificent old Oriental Theater. It was operated back then by the Pritchett brothers, who ran it as a calendar house. (This was before Parallax, and then the Landmark Chain took it over.) The programming was astonishingly eclectic. I practically lived there after classes in high school between 1977 and 1980, viewing (and, afterwards, over coffee or drinks at Von Trier’s across the street, reviewing critically with friends) hundreds of films. That was when my crush on cinema turned serious.

When I landed in Philadelphia and conservatory (where I dared steal little time for anything but composing and practicing the piano) at the Curtis Institute of Music, I began reading serious film criticism, devouring Truffaut, Bazin and the rest. Landing a few years later in Manhattan to complete my musical training at Juilliard, I was fortunate enough to have access to the Regency Theater, a fabulous calendar house at 67th and Broadway that showed old films, during its last few seasons. I even met Truffaut there at the end of a festival of his movies! Sometimes I think that leaving my composition lessons (which could be intensely stressful) and heading straight to the cool darkness of the Regency preserved my sanity. I was among the protesters out front when they closed it in ’87; the Thalia uptown closed the same year.

That opera world opened to me with the 1993 premiere of my first major opera, Shining Brow (on a libretto by Paul Muldoon about the tragic murders at Taliesin and the early career of Frank Lloyd Wright). I spent a little time in Los Angeles during the early 90s, met with some people, and made some connections in the film world. Had I not been fortunate to enjoy such relative success as a young composer in New York at the time—a commission from the New York Philharmonic, prizes, other opera commissions, a teaching job at a liberal arts college called Bard—I would have probably pursued film work then.

Instead, over the next twenty years I composed a dozen operas, a slew of symphonies, reams of chamber music, and hundreds of art songs. I became immersed in the east coast concert music world and fully embraced my life as a Manhattanite. A few years ago, my wife and I moved to the country to raise our children. Gradually, I began accepting invitations to serve as stage director for my operas. During production by Kentucky Opera of A Woman in Morocco at the Actors Theater of Louisville, it was pointed out to me that my theatrical staging was clearly filmic and that it was too bad that we weren’t making a Playhouse 90 out of it. Frankly, it had never occurred to me not to stage it cinematically. In hindsight, moving into film directing—making films—was my logical next move.

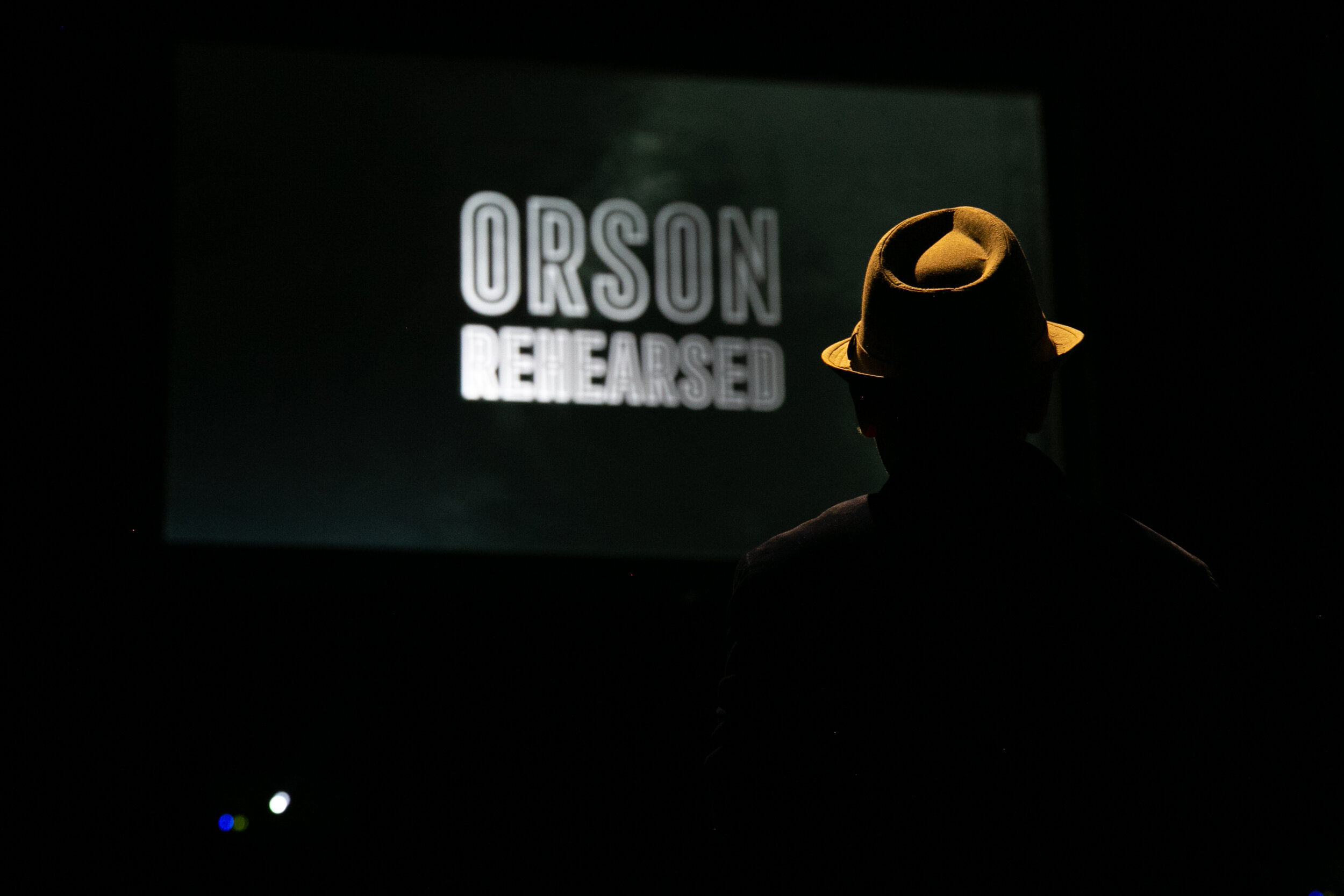

FCM: Orson Welles once said, 'The enemy of art is the absence of limitations". In Orson Rehearsed, you limited yourself to the stage and music. What kind of freedom or creativity did it bring?

DH: Welles’ comment echoes a paradoxical observation that Stravinsky makes in Poetics of Music: “My freedom consists in my … moving ahead within the narrow frame that I have assigned myself for each one of my undertakings.” Generating a rhetoric is my way of making a “sandbox” or “narrow frame” in which to frame narrative. Orson Rehearsed takes place in Orson Welles’ mind as he crosses through the bardo between life and what comes after. My challenge was to come up with a rhetoric with which to coherently explore the inner workings of one genius’ mind.

Since Welles worshipped Shakespeare, who described the world as a stage in As You Like It, I chose to have the stage of the Studebaker Theater in Chicago stand in for the interior of Welles’ mind. Analyzing Welles’ films from a Freudian standpoint (they were born on the same day) is something of a cottage industry among film-buffs; it occurred to me that dividing up his self-image into three avatars would be a sensible story-telling strategy: one would be the residual self-image of his rollicking youthful self; another the fully engaged artist of his middle years; and the third his present self, dying.

I needed a visual rhetorical language for expressing numerous layers of consciousness. Consequently, every one of the (repeated and recontextualized) images in Orson Rehearsed is synchronized to specific words, concepts, and musical ideas that are treated the same way. Consistent use of foreground, middle-ground, and background action in the frame allowed for having at least three things going on simultaneously much of the time.

I determined to express Welles’ ego by documenting the onstage action. I am indebted to filmmaker H. Paul Moon for suggesting that I wash out all the onstage footage—present it all in black and white. This really helped me to clarify the visual rhetoric of the film.

Stream-of-consciousness images generated by his id were displayed as three sixty-minute (full-color) movies projected above the heads of the three onstage avatars. These images would be treated as visual motives that would recur and develop over the course of the film—scraps of film leader, the wing of a jet flying through the night, playing cards, waves, hands at a manual typewriter or a piano keyboard, a boy’s hand tracing letters etched into a gravestone, candles on a birthday cake being blown out, a woman running her hands through her hair, waves transforming into clouds transforming into white static, an eye superimposed over the lens of a camera, a spastic puppet dancing, a red satin scarf that transformed into Rita Hayworth’s tossing hair, and so on. Depending on the focus of the narrative at any point, the images would come to the fore (as in the overture and several scenes), be intercut with other images, or confined in tightly framed boxes.

Welles’ “real-time” coming to terms with his imminent demise by way of his super-ego would be overlaid as semi-opaque images (screened either red, white, or blue and including an important bit of 30s stock footage of a boy walking away from the camera that stands in for Orson as a child) during the process of editing the id and ego narratives together for the filmic iteration of the work.

The musical rhetoric was derived from (and strictly synchronized with) the visual rhetoric. The electro-acoustic component of the score represented Welles’ id. Acoustic orchestra and the singer avatars were his ego. The composite soundtrack, recorded live in the Studebaker in performance (as I feel that live performance before an audience is the lifeblood of music-drama) so that the electro-acoustic and acoustic (id and ego) mixed naturally, manifested his super-ego.

The libretto, or script was organized in a similar fashion. Welles’ super-ego was expressed as old-fashioned “explanatory” onscreen intertitles framing the following scene, as scrolling text (the interview with Merv Griffin), the heartbreaking cri de cœurfrom Henry IV (“the true and perfect image of life”), and as a crucial revelation presented almost as an after-thought: “I had forgotten to wish for something.” His ego is expressed by the text sung by the onstage avatars, who sing mainly repurposed pertinent snatches of Shakespeare, (mis)remembered fragments of his interviews, radio broadcasts, and dialogue from scripts. His id erupts in samples of his own voice mixed into the electro-acoustic soundscape—from anguished utterances like “they destroyed Ambersons; the film destroyed me” to tender lines from a 1946 radio broadcast in which he gallantly compares Rita Hayworth to Helen of Troy.

FCM: Beside the screenplay, your film also has music and arias, and they must have taken you a long time to compose. How did the idea for the film come to you? How long did it take for the screenplay to take its final shape?

DH: The screenplay began as a collection of dramatic beats (I eventually created 52 of them, like a deck of cards). The twelve scenes that comprise Orson Rehearsed the film I chose in an organic fashion based on the forces I had on hand in Chicago only months before shooting. This process of throwing spaghetti at the wall (shooting about thirty hours of film for the onstage films, reading, collecting bits of dialogue and creating musical, visual, and textual material) took a year or so. I didn’t start to storyboard until I knew which “beats” I was going to use. This took about four months.

At this point, I still didn’t know exactly which order the scenes would happen. Once I had all the “id films” cut and a rough mockup of the score, I shaped them into a psychologically verifiable sequence. This of course prompted adjustments. Richard Strauss teaches opera composers that the drama happens mainly in the transitions: just so with Orson Rehearsed. The transitions were the anchoring points for the “super-ego” layer of rhetoric that binds together the narrative as a whole.

There are still forty more in various stages of completion on my hard drive that involve, among other characters, Rita Hayworth, Marlene Dietrich, Oja Kodar, John Houseman, John Huston, and Marc Blitzstein, among others. There are some loopy, surreal dream ensembles in them that would have made for a very different film.

From (l.to r.) Robert Frankenberry, Robert Orth, Omar Mulero, and music director Roger Zahab during discovery. (Neil Erickson photo)

FCM: Tell us about your experiences of working with your actors. How did you select them and what were the rehearsal sessions like? How long did you work with your actors before the filming began?

DH: I’d known for nearly a decade that I was going to write the role of the dying Welles for the legendary baritone Robert Orth. Bob was a fiercely capable, emotionally brave intellect and performer who could suavely straddle the American Music Theater and Opera traditions. The “go to” baritone for an entire generation of well-known American opera composers, Bob and I had first crossed paths when the terrific director Ken Cazan had cast him in a revival of Shining Brow with the Chicago Opera Theater in the 90s. As it happened, Bob was undergoing chemotherapy during the staging and filming of Orson Rehearsed. His performance was nothing less than heroic, and he passed away a few months after production. For the middle-aged Orson, I knew beforehand that I would write for Robert Frankenberry, a prodigious musical and theatrical polymath (conductor, tenor, stage director, composer, pianist) who I had cast as Louis Sullivan in the Buffalo Philharmonic’s recording of my Frank Lloyd Wright opera Shining Brow and who had gone on to conduct the orchestra in a revival of the opera in a site-specific staging at Wright’s Fallingwater a few years later. As a faculty member of the Chicago College of Performing Arts, which co-produced Orson Rehearsed, I was able to cast the young Orson with Omar Mulero, a gifted tenor and graduate student there, then just beginning his career.

Discovery for Orson began with the eleven live musicians—members of the Chicago-based Fifth House Ensemble—nearly a year before staging. As with the singers, I had no interest in crafting something avant-garde for its own sake, so I needed traditionally trained players who could stretch into new spaces. During several exploratory sessions, I learned how much creative risk each player could tolerate. One player, Eric Snoza, had acting training and slipped easily into the role of Jacaré’s ghost, playing his upright bass and interacting with Orth. In the end, I was able to ask the players to sing as a chorus of muses as well as play their instruments in a number of contexts; I asked for some minimal improvisation. In addition, they provided clouds of spoken dialogue that complimented and expanded upon phrases that they pre-recorded for me as a group and that I mixed into the electro-acoustic component of the score. I drew them as far out of their instrumentalist “comfort zones” as they were willing to go at the time.

Discovery for the Orsons, our musical director and conductor Roger Zahab, and myself, began a week before staging rehearsals and resulted in what I can only describe as the most fulfilling and honorable work I’ve done as an artist. On the most superficial level, it was a treat to “talk Welles” with them. They had of course done their homework and ascertained the sources of the real-life situations being dramatized/examined. On a deeper level, the technical exchanges—the relative ages of the instruments themselves and the cues and tricks the men shared with one another about how to manage vocal challenges, as well as the acting challenges inherent in singing opera and acting at the same time. The mentorship in rehearsal that Frankenberry and Orth gave Mulero was deeply moving to witness and a pleasure to transform into stage/film interaction. Still deeper, the fierce mutual trust and support that actors develop in order to shoulder the emotional trauma of their characters’ journeys. It was a great honor, for instance, to facilitate (as composer, librettist, and director) a process in which Bob, just arrived at rehearsal from a chemotherapy session, described an epiphany he had just experienced about how the dying Welles he was portraying may have felt.

FCM: Do you think there is enough space for experimental and independent films in the film industry today? How can these films reach a wider range of viewers? Are film festivals successful in introducing these films to the public?

DH: I don’t have an answer for that. I do sense that opera producers are all eager to make what they consider films now and to at least stream them. The “MET-Live in HD” success story is one thing: these are glorious documents of stage productions. With COVID having reshaped the entire idea of what constitutes live performance, opera companies in the States appears to now be seriously addressing the idea of creating productions staged expressly for the camera—as though we’d all been thrown back to 1951 and Amahl and the Night Visitors from Studio 8H, only on the Internet. Very exciting. The challenge for the opera folks is to do more than create more filmed stage performances. That is a new path forward that Orson Rehearsed is beating.

FCM: You have used many editing techniques in the film. The scenes get dissolved into the next ones, and double exposure seems to be used significantly. Did you shape the film into its current form during editing or did you have all of it in your mind in pre-production or during the shooting stage?

DH: The multiple exposures that run throughout the film were all storyboarded beforehand. The challenge was to find a way to wrestle the coverage I had on hand after the shoot into the hoped-for composite images. I was able to get about half of what I was after. The rest fell into place gradually, through exploration and gradual, deepening understanding of what the images were saying to one another. To me, the time spent editing film felt exactly the same as composing music does. That was a pleasurable revelation. Days before finalizing the project, I was still swapping out better shots in the “id” department as I stumbled on to them.

FCM: Was the music played live on the set or did you record it beforehand and singers sang over pre-recorded music?

DH: The singers sang over mockups during staging rehearsals. Once the live orchestra joined in (in the usual opera fashion, at the sitzprobe) the mockup was swapped out for the strictly electro-acoustic tracks crafted to combine with the live orchestra in performance. I have integrated pre-records for many years into my operatic scores, so I possess the specific skills required to craft something that didn’t require balancing and mixing in the theater. The singers did not wear lavalier microphones (this was important to me; I wanted to feel them fill the 1900-seat Studebaker Theater), and the orchestra was not close-miked. It was important to me that there be no recourse to ADR, and that there be no looping. What one hears on my final mix of the film soundtrack (and on the CD release forthcoming on Naxos Records in March) is very close to what the audience in the theater heard.

FCM: How long did it take to shoot the film? What were the problems or challenges you faced during the shooting stage?

DH: The films-within-the-film took about a year to shoot, assemble, and edit in tandem with the composition of the score. These were just a joy to create. Once we moved into the house, the onstage action was covered in four days: a dress rehearsal, a technical rehearsal, and two performances with stationary cameras moved around for various pre-planned shots, as well as two hand-held cameras getting close-ups and specialty shots. The principle practical challenge with getting the Studebaker Theater coverage was that I was serving as director of the staged production of Orson Rehearsed and had little time to manage the videographers. There was no DP, so I had to shape a lot of shots to as close to my original storyboard as possible after the fact in the editing bay on the fly from larger, lower-quality shots. There was simply no time to see what we had in the can and to reshoot, and there is only so much that one can fix in post. I will not make that mistake again.

FCM: In between the scenes on the stage, we see images of the space outside the stage area. The film marks a transition through these frames and yet it keeps its rhythm the whole time. How many of these frames were carefully constructed as a way of strengthening the overall ideas behind the film and how many of them were simply a mixture of abstract (or random) frames?

DH: The transitions between set pieces was where the super-ego and id narratives came to the fore, and were storyboarded only a month or so before shooting because I didn’t finalize the sequence of scenes until shortly before production began. I retained about half of what was preplanned when I finally edited the final cut together; sometimes a better way of moving things forwarded presented itself, so I swapped in that visual material instead. The rhythm of the film remained stable because I edited the images to the score, which was frozen in time first. So, yes, they were carefully constructed: just as in composing opera, transitions perform the most dramaturgical heavy-lifting and their rhythm is the hardest part to get right. They’ve got to seem improvisatory and inevitable, and one has to learn how to craft them so that they seem so whether they are or not.

FCM: Tell us about the reaction of those who saw the film. What did they think about it?

DH: Not very many people have seen it yet. I’ve been intensely grateful for the appreciative response I’ve had from admired colleagues like John Corigliano, and from film composer colleagues I’ve long admired and whose work I’ve closely followed. Aficionados of Welles’ work are invariably supportive. I’ve received invaluable advice from film editor Rabab Haj Yahya, director David Gideon, and others, and remain very grateful and moved for the staunch support of the Chicago College of the Performing Arts, on whose Artist Faculty I am proud to serve. I am thinking of this film the way that a poet thinks of a poem and a serious opera composer builds an opera: it is dense, highly allusive in its methods, and it benefits from repeated viewings; Orson Rehearsed delves with subversive lightness into some pretty dark and scary places. I am not expecting it to be “popular” in any sense of the word; it is an “art film,” that will land with people who bring an open mind and heart to it.

FCM: Are you currently working on another project? What will be your next film?

DH: I’ve got several projects already in pre-production that carry forward the methods (combining music and image, film and live theater) I’ve been steadily digging into over the past 20 years. I’m slated to direct a filmed version of my opera Shining Brow at the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Westcott House with the Springfield Symphony and Think TV (the Dayton PBS affiliate) next year. I’m also filming my next film/opera 9/10, set in an Italian restaurant in Little Italy the night before the Twin Towers fell, in Chicago, in spring 2022 in another Chicago College of the Performing Arts-New Mercury Collective co-production. I’m taking things as they come and scaling things in order to match vision and budget sensibly. My ultimate goal is to gain complete fluency in the idiom and to work at the highest levels with collaborators from whom I can learn the most.

Please visit Fullshot Cine Mag to read the interview in its original context here.