William Weaver was one of my closest faculty friends during the decade I taught music composition at Bard College. The eminent translator of works by Umberto Eco, Primo Levi, and Italo Calvino, among others, Bill also worked as a commentator on the Metropolitan Opera Broadcasts, and made exquisite libretto translations. His monographs on Puccini and Verdi (The Puccini Companion, and The Verdi Companion) continue to serve as irreplaceable resources for me as an opera composer. Wednesday evenings when I wasn’t drinking with my department chair, I either spent with harpsichordist and Frescobaldi-expert Frederick Hammond, or over pasta and champagne with Bill and his emotionally mercurial Japanese partner Kazuo Nakajima at the house they shared on campus in which Mary McCarthy used to live. I learned more about dramaturgy from Bill over dinner during those years than from anyone else. To dine with him was, in a way, to dine with Callas and the rest; only two other men I’ve known could match his operatic erudition: Speight Jenkins and Frank McCourt. He also taught me how to make an exquisite Pasta Puttanesca in less than five minutes.

Bill also maintained a villa called Monte San Sevino (on to which he had built an addition with royalties derived from his translation of The Name of the Rose that he called his Eco Chamber) and an apartment close by St. Vincent’s Hospital in Greenwich Village. Over dinner in his Village pad in autumn 1995, Bill asked me, “Do you know any poetry by Jimmy Merrill?” I did. Merrill, one of my favorite poets, had succumbed to AIDS only the previous February. I had read The Changing Light at Sandover in high school, and it was my good fortune to have from memory his Kite Poem. I closed my eyes and recited it, concluding:

Waiting in the sweet night by the raspberry bed,

And kissed and kissed, as though to escape on a kite.

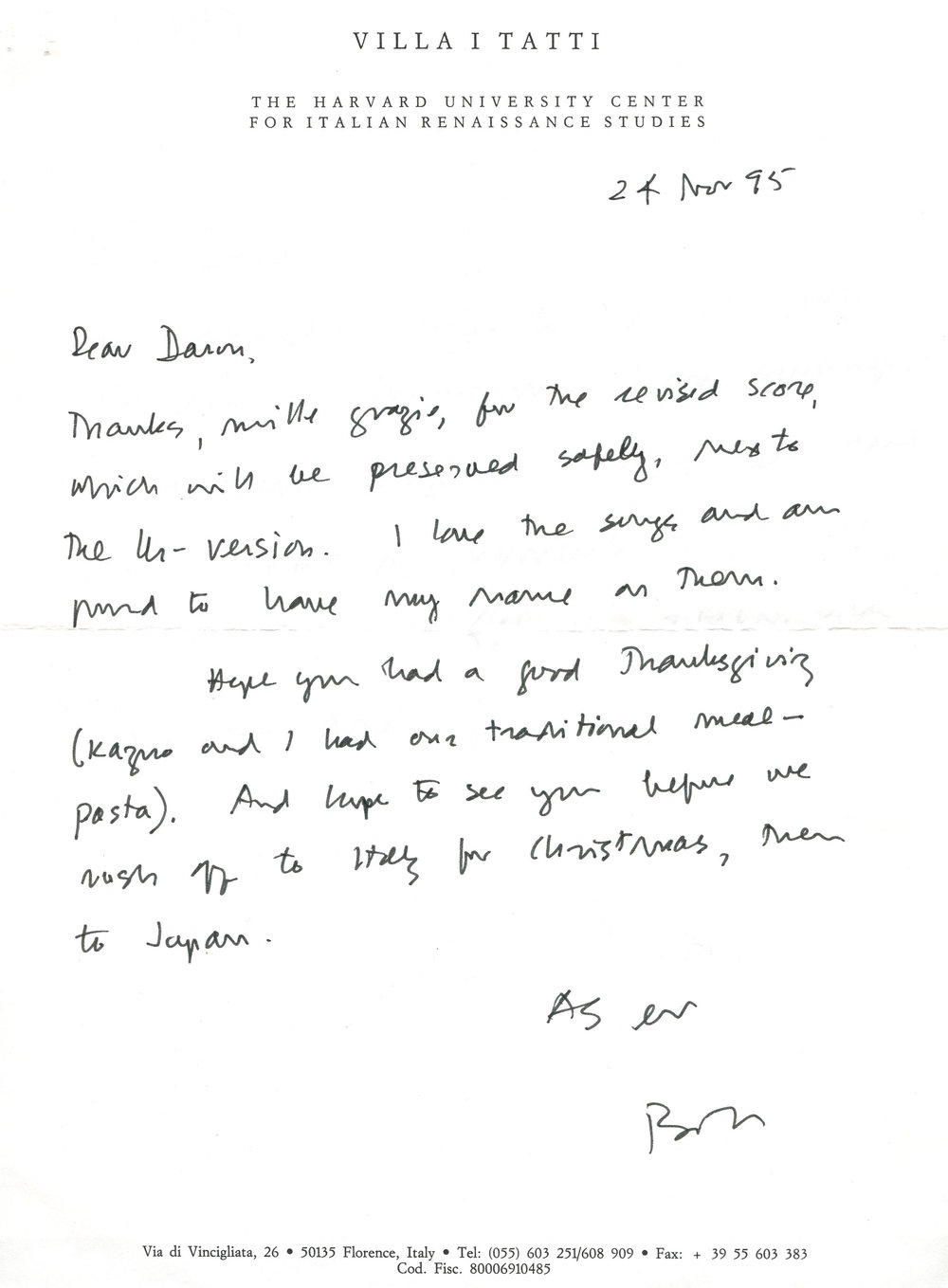

When I opened my eyes, I saw that Bill was weeping. “Did you know him?” he asked. “No,” I said. “I never met him.” Beat. “Well,” Bill sighed, looking down. “I have a proposition for you: I’d like to commission some songs in Jimmy’s memory. I also have a young protégé named Charles Maxwell—a countertenor—who I’d like you to hear. If you like his voice, then I’d like you to premiere them with him.” Flattered, honored, I agreed immediately. “But the rights—,” I began. “Oh, just ask Sandy McClatchy to release them,” he said. “He’s Jimmy’s executor.” I waited. “How much will you need for the work?” he asked. Uncomfortable, I looked down. “Let’s do this,” he said, smiling. He reached in his jacket pocket and drew out a little notepad. Ripping off a blank page and sliding it across the table to me, he said, “Why don’t you write down on this piece of paper how much you need?” I did as I was told, wrote down a number that I thought was reasonable, folded the paper, and slid it back to him. Smiling, he opened it, read the number, put the paper down, drew his checkbook from another jacket pocket, and wrote a check. Still smiling, he ripped the check from the book, folded it carefully in half, took a sip of his chianti, and slid it back to me. I put it in my breast pocket without opening it. “Now!” he clapped his hands. “Let’s have some dessert!” An hour later, walking to the subway, I thought to draw the check from my pocket: he’d given me exactly twice the amount for which I’d asked.

I had at the time the impression that composing for a male soprano was pretty much like writing for any other singer, but I was wrong. Writing for Charles Maxwell, I learned just how much physical strength and stamina is required to sustain singing for any length of time an octave higher than men customarily do. An African-American born in North Carolina, he projected the intelligent, elegant, self-contained dignity of one who had endured and overcome bigotry at home before emigrating to Italy, where he completed his studies at the Instituto Musicale “P. Mascagni” in Livorno. We debuted my Merrill Songs together at the Danny Kaye Playhouse in Manhattan the following November on a Clarion Concert, thanks to Fred Hammond—Fred had taken over as director of them as a favor to his mentor, Ralph Kirkpatrick. I was so intrigued by the otherworldly appeal of Charles’ voice—it retained its brilliance and clarity even in the extremely high register without ever losing its volume—that I subsequently suggested to my librettist collaborator Paul Muldoon that we make the character of Vera in our new opera Vera of Las Vegas a female impersonator—personal reinvention was to be the core theme, and playing The Crying Game’s trope seemed an apt starting point—so that I could craft it especially for him.

Bill died several years ago, not far away from where I now live, and I miss him dearly. This morning, as I scrolled through the latest McCarthy-esque prattling in the news, I thought suddenly of that dinner with Bill in 1995. I looked up from my chair and my eyes rested on the spine of his Puccini Companion a few feet away on the bookshelf. I felt gratitude for having had the good fortune to have witnessed firsthand the understated elegance of his transit through life. I felt gratitude for having been able to enjoy—over a hundred Metropolitan Opera broadcasts over the years, and a few dozen meals—his frank intellectual brilliance. I felt gratitude for the humble, gentlemanly dignity with which he confronted the challenges of both Art and Life.

This piece originally appeared in the Huffington Post. Click here to read it there.